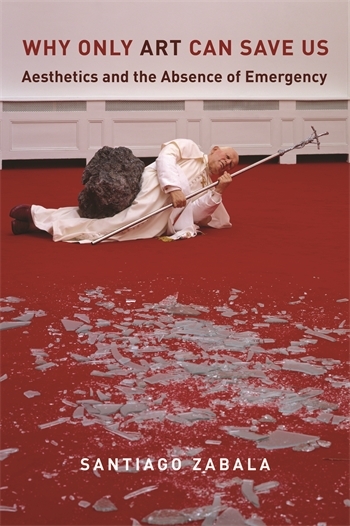

Why Only Art Can Save Us, Part II

The following is part II of an interview with Santiago Zabala, author of Why Only Art Can Save Us: Aesthetics and the Absence of Emergency. You can read part I here.

Question: Heidegger’s Schwarze Hefte (Black Notebooks) have an important place in your book. Can you explain why? Aren’t you afraid of the anti-Semitic passages of this book?

Santiago Zabala: The reason I used these books is that they contain, as his other writing of the same epoch, a number of statements on emergency and its absence that are central for my research. As far as the anti-Semitic passages: I obviously condemn them, but they don’t have much to do with his philosophy. Let’s please remember Heidegger is not the only great philosopher to have racist and antidemocratic views: Aristotle justified slavery, Hume considered black people to be naturally inferior to whites, and Frege also sympathized with fascism and anti-Semitism. Although Heidegger’s involvement with the Nazi Party has been known since the late 1980s, the recent publication of his Black Notebooks offered more evidence of his racist (anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic) views, triggering a backlash. If Jürgen Habermas, among others, has recently expressed perplexities regarding the ongoing fascination with Heidegger’s Black Notebooks, it’s because the attempt to channel his anti-Semitism into the history of Being is absurd. It’s part of what David Farrell Krell calls the “Heidegger scandal industry.” Together with other Heideggerians such as Krell, Richard Polt, and Gregory Fried, I think it’s important to continue to both read and criticize his philosophy despite his unacceptable racist views.

Q: Besides Heidegger, which other philosophers help you to create this new aesthetics?

SZ: Arthur C. Danto, Jacques Rancière, Gianni Vattimo, and Michael Kelly have all contributed in different ways. Danto, through his theory of the end of art, has helped me understand how truth has become more important than beauty; Rancière showed me that aesthetics is irreducibly political in its distribution and imposition of the sensible; and Vattimo indicated the hermeneutic consequences of art’s ontological status. Kelly, it could be said, triggered the whole project. In A Hunger for Aesthetics he writes that “the main goal of aesthetics today is to explain how the transformation of demands on art to demands by art is already a reality in some contemporary art.” These demands are linked to the absence of emergencies produced by our metaphysical condition. This is why aesthetics must be capable of interpreting these demands rather than “reality.”

Q: By “reality” you are referring to so-called speculative or new realist aesthetics that seek to judge or describe works of art independently of their effects, environment, and relations?

SZ: Yes, although I would not call “new realism” a new philosophy but the latest descriptive metaphysics. The adherents of this movement are brilliant at marketing it through book series, conferences, and blogs, making the public believe it’s something new, but they embody the absence of emergency we discussed earlier. Although these “new” philosophers justify their theoretical beliefs in different ways, seeking to demonstrate—despite Thomas Kuhn—the supposed stability of a particular scientific understanding of the world, their work is part of a global call to order or, as Boris Groys recently pointed this out in E-Flux, a return to psychology and psychologism. It is curious, as Simon Critchley rightly pointed out, that just “when a certain strand of Anglo-American philosophy (think of John McDowell or Robert Brandom) is making domestic the insights of Kant, Hegel and Heidegger and even allowing philosophers to flirt with forms of idealism, the latest development in Continental philosophy is seeking to return to a Cartesian realism that was believed to be dead and buried.” If, as Graham Harman suggests, aesthetics ought to become “first philosophy,” it is not because it can understand the “cryptic inner reality” that makes the effects of art possible, but rather because aesthetics can provide a way to interpret the emergency of art’s existential disclosures. After all, as Žižek says, “there is no ‘neutral’ reality within which gaps occur, within which frames isolate domains of appearances. Every field of ‘reality’ (every ‘world’) is always-already enframed, seen through an invisible frame.”

Q: Is this “invisible frame” what you call hermeneutics? What role does the philosophy of interpretation have in the book?

SZ: Yes, interpretation is the invisible frame through which we understand the world, and ignoring it is simply silly at this point of the history of philosophy. Hermeneutics is a philosophical stance focused upon the interpretative nature of human beings. Although juridical and biblical hermeneutics played a significant role throughout the history of hermeneutics, Hans-Georg Gadamer, in Truth and Method, decided to emphasize its aesthetic nature. Instead of its aesthetic nature I stress interpretation’s anarchic nature. The interpretation required to draw us closer to genuine appearance must be anarchic and existential, that is, suited to “venture into the untrodden and unformed realm of the opening of the emergency” as Heidegger says. If we can save ourselves through art’s existential claims it’s because interpretation is a vital practice where the interpreter, as Vattimo says, “must also become, fatally, a militant.” In sum, this book develops a radical hermeneutic conception of art and aesthetics by way of a philosophical and political engagement with Heidegger, as well as with contemporary artists who help demonstrate and apply this vision.

Q: For the cover you chose an image of The Ninth Hour, the most celebrated sculpture by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, which represents Pope John Paul II lying on the ground after being struck by a meteorite. Can you explain how it relates to the book?

SZ: The sculpture’s title alludes to the ninth hour of darkness that fell upon all the land when Christ cried out “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?”—“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This alludes to this book’s title, which paraphrases Heidegger’s famous statement that “only a God can still save us” when he was asked whether we could still have any influence now that we are so overpowered by technology. Heidegger alludes not to God’s representative on earth, as portrayed in Cattelan’s work, but rather the absence of Being, which in our technological world has become the essential emergency. The goal of this book is to thrust us into this emergency as it is revealed through works of art. I was very happy to see this sculpture also used in the opening credits of Paolo Sorrentino’s The Young Pope series, which I enjoyed very much.

Q: Beside Cattelan’s work on the cover, there are twelve works in your book by artists from all over the world. Can you talk a little about why you chose these particular artists? Aren’t you afraid, as Mark C. Taylor said, that art often “loses its critical function and ends up reinforcing the very structures and systems it ought to be questioning.”

SZ: I agree with Taylor. But the same goes for philosophy or other intellectual activities. In order to challenge the lack of emergency in today’s society it is necessary to understand that these emergencies concern all of us. I’m referring not only to climate change but also to social media and global terror. I do not think that among artists there is greater freedom than among philosophers. How framed we are within the “very structures and systems” we should question does not depend on our field of research but rather how much we are inclined to disclose the absence of emergency. This is why I agree with Heidegger when he said the “artist remains something inconsequential in comparison with the work—almost like a passageway which, in the creative process, destroys itself for the sake of the coming forth of the work.” My choice of these artists or, better, their works, is not based on their nationality but rather in these emergencies. I think most of the artists were quite surprised by my request to use their work in the book as I’m not in the art world, a curator or an art critic. Either way, I’m very grateful they allowed the reproduction of their work.

Q: Why did you only present visual works or art?

SZ: Because they were easier to reproduce in a book. They are not necessarily better at disclosing the essential emergency than other forms of art such as dance, music, or cinema. I do refer to TV series (Hung), theater (Young Jean Lee’s plays), and songs (Tom Waits’s “The Road to Peace”) that also disclose emergencies.

Q: Some critics believe “relational aesthetics” is over. Has the time arrived for an “emergency aesthetics”?

SZ: I’m not certain whether the time is right as I’m not an art historian. Either way. I took my chances as I think the works of art I discuss disclose “an emergency turn” or “sensibility” in contemporary art. The problem is what we understand as an emergency. What is important for me is that the traditional relationship among the art object, the artist, and the audience is not simply overturned, as in relational aesthetics, but also disturbed, agitated into new action by the danger revealed by art’s ability to thrust the viewer into emergency. This move toward emergency art has also given rise to similar aesthetics theories, such as Jill Bennett’s “practical aesthetics,” Veronica Tello’s “counter-memorial aesthetics,” and Malcolm Miles’s “eco-aesthetics,” where emergencies also play a central role. The theoretical proposals of Bennett, Tello, and Miles, like my own emergency aesthetics, do not simply regenerate aesthetics through artistic practices but also respond to current vital issues. Hal Foster’s latest book, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency, confronts the problem of emergency, but he does not distinguish between emergency and absence of emergency.

Q: Does your book have anything to do with the Emergency Biennale?

SZ: I don’t think so. I learned about the biennale while I was writing the section on Jota Castro work’s in chapter 2. He created the biennale together with the curator and critic Evelyne Jouanno in order to draw attention to the suffering in Chechnya. While I find their biennale interesting, I’m concerned with a variety of emergencies, not only the one in Chechnya. But events like this biennale are important as they embody the “globalization of the art world” that Danto talks about.