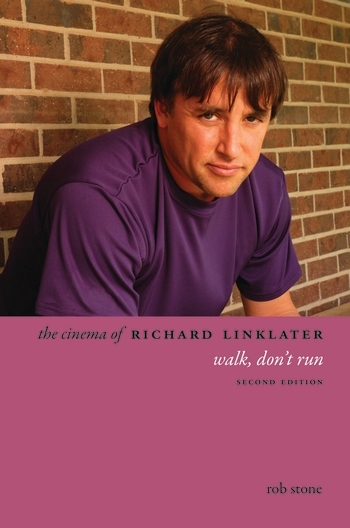

A Richard Linklater Moment — Rob Stone

The following is a post by Rob Stone, author of The Cinema of Richard Linklater: Walk, Don’t Run. You can also read an interview with Rob Stone discussing the book and Linklater’s films:

When the British-Canadian film scholar Robin Wood wrote about Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995) in his book Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond (Columbia University Press, 1998), he felt compelled to preface his analysis with the admission that “here was a film for which I felt not only interest or admiration but love” (1998: 318). His subscription to the kind of affective or appreciative criticism advocated by André Bazin sets a challenge for academics who commonly assume that the intellect must explain away intuition and that objectivity is our prime objective. Like many academics I was a closeted film fan allowed out to play with movies like Before Sunrise following the example of Wood, who not only shared his passion but made it an essential component of his craft.

Truth be told, I wasn’t expecting much. I was living in Madrid at the time and used to frequent the art house cinemas off the Plaza de España and just see whatever was on. Yet, as the film started, the feeling crept up on me that the world was changing. I’d done a lot of inter-railing around Europe so I knew the sensation of timelessness in travel and the everyday fantasies of actually connecting with someone who was going the same way as you; but Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Céline (Julie Delpy) somehow ignored the fear of rejection and amazingly invited me to travel with them too. At first, I admit, I observed them, sometimes cringing at the conversation but mostly admiring the eloquent dialogue that culminates in some convoluted argument about time travel that Jesse uses to convince Céline to get off the train with him in Vienna. There they walk, talk, drift into a record store and try out a listening booth. And then this happens:

It’s been eighteen years since I first shared that song, that booth, that moment with Jesse and Céline and the feeling has never gone away. Indeed, the sensation has only intensified by reconnecting with them in the Paris-set sequel of Before Sunset (2004) and their (our) present-day reunion on a Greek island in ‘Before Midnight’ (2013). Lacking Wood’s courage, I’ve often tried to understand (and perhaps disguise) my love for this scene in analysis, bolstered by the fact that it even lends itself to academic enquiry by combining two of the most evocative themes in film studies: time and the gaze.

The scene in the booth is a single take that promises to last as long as the song, which lends itself to the notion that music and film commonly share and express the ability to make time malleable and its passing tangible. Film studies has taken a turn for theorizing rare moments such as these, when, as the theorist Gilles Deleuze observed in Cinema 2: The Time-Image, “a little time in the pure state rises up the surface of the screen” (2005:xii). Time and time again, the cinema of Richard Linklater teaches us that the consciousness of self is divided into the intellect or ‘mind’, which is rational thought, order and consequences, and intuition or ‘heart’ that is a sense (perhaps a knowledge) of living in the moment. However, whereas thought plots present-moment choices in terms of long-term consequences that may never happen, feelings make immediate choices which do. The heart is therefore more rational in a sense because it deals with reality whereas the mind is always constructing fantasies. In the time it takes to confirm the reality of this faintly ludicrous situation and fantasize about where these genuine feelings might lead, this single shot in the listening booth arguably combines the two.

Moreover, the reality/fantasy of being cramped together in a listening booth is paradoxically a privileged position. Céline and Jesse take chancing glances and look away, but it seems we never have to. Instead, we feel able to look at them both and admire what they signify: that is, the potential of youth, which is reclaimed in Paris nine years later and longed-for by the time they get to Greece. Following Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1973), which shifted film theory towards psychoanalysis, film studies binged on the cinematic gaze, finding that the art of watching and the compulsion to look was tied up in innumerable systems of meaning. Yet the gaze through which we experience our threesome in the tiny booth is neither voyeuristic nor fetishistic, but participatory. In truth we do not take in the whole frame and see Jesse and Céline at the same time; rather, we too look at one and then the other, which suggests that maybe, just maybe, at one moment or another, while we are watching Jesse, for example, Céline might be looking at us..

I’ve never been able to catch Céline looking at me, but have enjoyed this sublime scene so many times that it’s never enough. Whenever I give a paper about film that references time, the gaze or the cinema of Richard Linklater, I try and include it as a clip. The pleasure then is not to watch it, however, but to observe the audience instead. Those who know it are already grinning and those who don’t are in for a treat. Like bringing out a bottle of single malt, this clip has made friends for me in many places. And of course, because Linklater insists on revisiting these characters every nine years, the romance never ends, but deepens. ‘Look at this, this is beautiful!’ says Jesse as they head out into the dusk, the song is appropriated by the soundtrack and the music becomes more classical and ageless, thereby commemorating the experience of an unrepeatable yet eternal moment in which we too shared and fell in love.

1 Response

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Let’s now attempt to examine some characters as they appear more or less sequentially in the novel, and take a look at the thoughts that go through Corde’s mind about each, and into which of James’ two groups they may be placed. Some characters, such as the Colonel or the Ambassador, obviously go into a category without much need for analysis of their thoughts and actions; others, such as Minna and Vlada Voynich, are actually hybrid personalities exhibiting strong signs of both personality designations.

http://bravenewclimate.com/2013/05/02/100pc-renew-study-needs-makeover/#comment-223214