Becoming Way Too Cool: How Neoliberalism Alters How We Feel

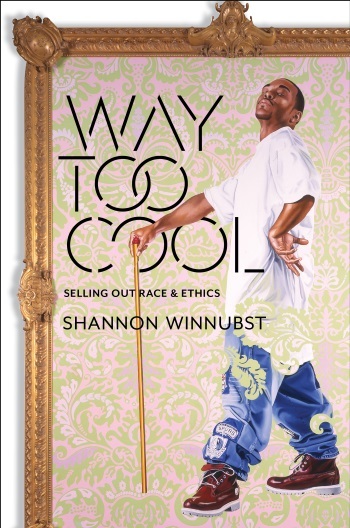

The following is a guest post by Shannon Winnubst, author of Way Too Cool: Selling Out Race and Ethics.

Becoming Way Too Cool

(How Neoliberalism Alters How We Feel)

Shannon Winnubst

I remember when my grandmother learned to use the word “cool.” It must have been about 1982 and, at 83 years old, she spryly pronounced my new shirt was “cool.” Stopped short, I caught the twinkle in her eye and proudly agreed. Little did we both know that we were in the grips of the rapidly ascendant neoliberal marketing machine.

“Cool” has been big business for a long time now. Pilfered from black culture by the men’s clothing advertising industry in the late 1970s, “cool” has packaged just about every commodity on the market at one time or another—and still continues to do so. Youth culture, especially, seems never to lose its connection with this heartbeat of energy. “Cool” has become a kind of naturalized constant in 21st century marketing cultures: we are so drawn to it that we cannot imagine otherwise. The quest to be “so cool” seems never to die.

But “cool” didn’t always refer to the latest, hippest thing. In the U.S., “cool” was born in post-World War II aesthetics of black culture, especially jazz. It captured and galvanized the kind of ironic detachment that enabled black folks to persevere in the face of systematic, persistent racism and its everyday violence. It energized black folks not only to survive, but to create and believe in something better. When Miles Davis stood up to racist cops and bigoted television show hosts, he was enacting the essence of cool: the kind of strong, determined detachment from racist mainstream culture that enabled intense creativity and the strength to flourish. This kind of “cool” is what bell hooks identifies in black leaders such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. as the strength to “alchemically change pain into gold.” The birth of “cool” was the birth of an ethical detachment from the hostility and violence of a racist world that carved the space for a better, more just world.

But in the endless marketing and celebrating of all things cool, we have lost touch with those roots of resistance to racism. And, in so doing, we have lost touch with their ethical valence. When everything is judged by “how cool” it is, we lose the capacity to discern the worth of anything: if something must first be “cool” in order to be “good,” then we no longer know what “being good” really means. Moreover, the erasure of these deep roots of “cool” as specifically a way of resisting the banal violence of racism is eroding our ability to make sense of “ethics” at all. It is this twinned erosion of resistance to racism and ethical discernment that drove me to write Way Too Cool: Selling Out Race and Ethics.

I began writing Way Too Cool because I wanted to understand as precisely as possible what this thing, “neoliberalism,” is doing to us. As I ploughed through reams of books on the subject, I got more and more bothered by how we are beginning not only to think like neoliberals, but even to feel like them: neoliberalism is becoming a way of living and feeling, not just some abstract set of economic policies. It is, in psychoanalytic language, altering our modes of cathexes, not merely the objects of them. The history of “coolness” and its bastardization from roots in black resistance to vacuous poses of detachment packaged by advertising moguls capture these social and affective changes perfectly. Coolness thereby became the perfect trope through which to investigate how we in the overdeveloped world are enacting and even embodying neoliberalism, understood as a social rationality, in largely unconscious manners.

It is not surprising, therefore, that we can see these dynamics directly in the ways we now try to deal with race and racism in the United States. As a culture as a whole, we seem remarkably confused about race and racism. On the one hand, we are endlessly told by teachers, sit-coms, politicians, preachers and news anchors that we live in a post-Civil Rights age where we now celebrate diversity: diversity is cool—and racism is dead. But underneath all that, we know better—or, thanks to the amazing persistence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, we ought to know better. We know—or ought to know—that we still live in a deeply, systematically racist culture that segregates us into racially determined neighborhoods, schools, zip codes, workplaces, and viewpoints. We ought to know that, despite all the rhetoric about the black middle class, the wealth gap between white and African-American families nearly tripled, increasing from $85,070 in 1984 to $236, 500 in 2009.* We ought to know that the “ghetto tax” has been systematically levied in the industries of auto insurance and housing mortgages since the mid-1960s to enforce the long-standing racist stratification of the United States through facially neutral practices (such as zip codes).** We ought to know that the explosion of mass incarceration, which overwhelmingly targets African-American populations, emerged simultaneously alongside the political movement to legalize same-sex marriage, thereby extending the rights stripped from non-white populations to non-straight populations and sidelining the issue of systematic racism yet again. We ought to know all of this and so much more. But it isn’t cool to talk about any of that. It is cool to ignore the entire situation—to push it further and further into our collective unconscious. It is cool not to know what race is or why it is the ethical question of our age.

As the brief history of cool I sketch in the book shows, the deracialization of the meanings and postures of cool occurs through stripping any historical or politicized connotation from them. Coolness is emptied of any content, rendered a formal stance of ironic detachment that does not materially stake any claim to “something better, something more.” Striking the pose of “cool” becomes a purely formal, empty gesture: the detachment in the name of resistance becomes detachment for detachment’s sake. One is now only cool if the pose is scrubbed free of any meaning, especially any past meaning about racism or resistance. Coolness lures us into its empty space and hollows out caring at all: the cooler we become, the less we actually care about what is really happening in the world, ethically or politically or historically or at all. The transformations are banal and profound: this twinned erasure of racism and ethics is the heart of the neoliberal social maelstrom. We are fast on our way to becoming way too cool.

* Shapiro, Thomas, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro. “The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide.” Institute on Assets and Social Policy Research and Policy Brief, February 2013.

** Fergus, Devon. “The Ghetto Tax: Auto Insurance, Postal Code Profiling, and the Hidden History of Wealth Transfer.” In Beyond Discrimination: Racial Inequality in a Post-Racist Era, edited by Frederick C. Harris and Robert C. Lieberman, 277-316. New York: Russel l Sage Foundation, 2013.

1 Response