The Russia of City Folk and Country Folk

Enter the City Folk and Country Folk Book Giveaway here

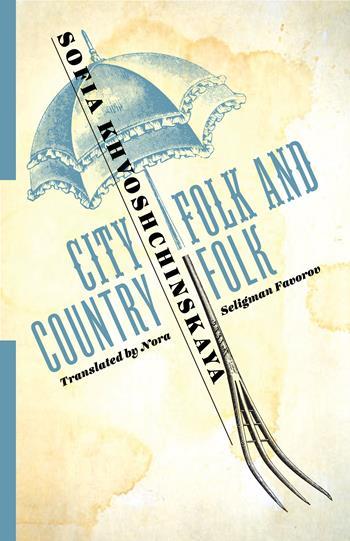

Welcome to the Columbia University Press blog! This week we are featuring Sofia Khvoshchinskaya’s City Folk and Country Folk, which has recently come out in Nora Favorov’s translation in the Russian Library series. Today Elaine Wilson, a PhD candidate in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Columbia University, delves into the historical backdrop against which the novel plays out.

The concept of separate spheres—distinct realms appropriate for male and female sexes, public and domestic, respectively—was widely accepted in the 19th century western world, Russia included. Still, in contrast to many European societies at this time, the number of rights guaranteed by law to Russian (upper class) women was rather significant; even prior to the reforms enacted by Tsar Alexander II, women of the privileged classes could exercise economic independence, own and manage property, issue lawsuits, engage in business transactions, and even file for divorce (Pushkareva). But while Russian women enjoyed more rights and protections than their European counterparts, they were far from privileged citizens. One need only look to the language of the Code of Laws to understand these rights were granted within a larger socio-political framework that ultimately upheld the idea of a woman’s separate sphere and her limited ability to participate in society. The role of the judiciary was to “protect the honor and tranquility of women” from “insults” and free them “from responsibility for some obligations in which they could become involved because of inexperience and gullibility” (Pushkareva). Such language matches the sentiments of Count Pyotr Andreyevich Shuvalov, counsellor to Alexander II during the 1860s and 70s and author of the quote above. But while Shuvalov’s remark is indicative of the predominant patriarchal attitude at the time, it is also reactionary to another question that occupied Russia with increasing urgency amidst the reforms of the mid 19th century: what roles could and should women play?

The answer—and society’s approach to the question—were evolving, right along with ideas regarding other kinds of social and political issues. It is within this changing climate that Sofia Khvoshchinskaya lived and wrote, and these shifting social and political attitudes shaped the characters and circumstances that appear in her works and provide important context for her novel, City Folk and Country Folk.

Under Alexander II, Russia experienced many significant changes, from the abolition of serfdom and greater investment in infrastructure and industry to reforms within the judiciary and educational system. These renovations were steps toward modernization, facilitated in large part through the establishment of local assemblies, or zemstva, which saw to the administration of regional affairs and local welfare. Alexander II’s new policies were generally considered to be a means of enlightening the countryside, though their reach was sufficiently broad that Russian society as a whole underwent a paradigm shift.

The abolition of serfdom in 1861 brought centuries of feudal agricultural practices to a halt and sparked new social and economic realities; in the 19th century, the majority of Russian subjects lived in rural areas, and four fifths of that rural population consisted of serfs and the peasantry (Curtis, 34). The serfs, newly freed, were obligated to pay the government for the land they received (most often a portion of the land they had always worked) through a series of “redemption payments” over the course of forty-nine years. In 1860s Russia, agriculture was not sufficiently advanced to accommodate large scale farming, and only a small percentage of land was truly arable. Even when they were still legally tied to an estate, most peasants had only survived through subsistence farming. Upon emancipation, this limited agricultural output posed a problem, both for the peasantry and the government. Peasants began their lives of freedom deeply in debt with no recourse for stability, much less economic growth; the government, which had hoped the peasant farmers would use their land to feed themselves and cultivate food for export, found itself still unable to pay off foreign debt and burdened with new economic complications (Curtis, 34).

Landed nobles likewise suffered financial losses. Many members of the aristocracy who owned homes in the country did not live on these provincial estates, but rather maintained the land and its properties as distant assets, entrusting their management to someone else. With the abolition of serfdom, these landowners (many of whom infrequently visited their estates), effectively lost a portion of their assets. The government issued bonds to landowners whose serfs were freed, but as the peasants failed to make redemption payments and the government accrued more debt, the value of these bonds fell dramatically. Those landowners who could neither farm nor manage their estates sought to shed their losses and sell their country holdings.

In Sofia Khvoshchinskaya’s fictional village of Snetki, many of the country estates have been accordingly affected by agricultural reforms. The novel’s principle male protagonist, Erast Sergeyevich Ovcharov, “had not looked in on his property for many years, and upon arriving he discovered that he could not possibly live there. The manor house had long since been sold and carted off to town” (Khvoshchinskaya, 7). His walk through the village reveals that many of his neighbor’s homes have met similar fates:

“The cluster of houses was devoid of life. He walked past one of the manor houses built right on the road. The house, its windows boarded up, was gray and utterly lopsided. Of course, it had once been surrounded by outbuildings, but now it sat amid wasteland; only crumbling brick rectangles, overgrown with wormwood and nettles, hinted at the foundations of past structures.” (Khvoshchinskaya, 10)

Ovcharov’s initial impressions upon his return to Snetki are set in stark contrast to the vibrant, idyllic recollections of the summers of his youth. But these estates which have fallen into ruin also underscore the success of Nastasya Ivanovna, the sole remaining landowner in Snetki whose careful management has allowed her house and its inhabitants to maintain a comfortable life. Upon entering Nastasya Ivanovna’s foyer, “Ovcharov noted that it was clean, whitewashed, and orderly. Unlike nine-tenths of rural entrees, it was not cluttered…. This cleanliness made a pleasant impression on Ovcharov, who rightly concluded that the rest of the house and Nastasya Ivnovna’s entire estate were kept in a similar order” (Khvoshchinskaya, 16).

Nastasya Ivanovna is not the only female character notable for her success in a changing era. The Malinnikov sisters—whom we never see—are former Snetki residents who have taken to supporting themselves through translation and writing stories and articles. These women serve as a kind of novelistic cameo for the author and her sisters who worked as authors and translators themselves. But in the context of the story, the hushed tones and subtle sense of scandal surrounding the mademoiselles Malinnikov aren’t just a playful bit of self-effacing humor—Khvoschchinskaya uses this autobiographical nod to illustrate the absurdity of the moralizing attitudes of the era.

“Mademoiselles Malinnikov—one is thirty, the other thirty-five years old—and they are both writers.”

“And at this point, they won’t be getting married,” Nastaya Ivanovna lamented.

“Why not, Nastasya Ivanovna?” Ovcharov asked, noting that his hostess’s verdict had less to do with the ages of Mademoiselles Malinnikov than their vocation. (Khvoshchinskaya, 23)

Absurdity is a common component of many scenes in the novel. At times the characters engage in discussions so silly that they could pass something out of a Monty Python sketch (see the conversation regarding the relative virtues of Swiss and Circassian whey in Chapter 1).

All characters are not unaware of the absurdity, however; Nastasya Ivanovna’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Olenka, rarely makes an appearance without a smirk or a laugh. Young and willful, Olenka embodies the growing sense of independence and choice among women of her century, a foil for the pseudo-intellectual and arrogant Ovcharov, a man with pretensions of “liberating” the women of Snetki through the newest, most fashionable spin on centuries-old misogyny. Indeed, all of the characters of City Folk and Country Folk can be said to represent one of the prevailing attitudes of the changing social reality of 19th century Russia. It is helpful to keep in mind then, exactly what kinds of external factors helped to shape them and the changing landscape of their world.

Curtis, Glenn E. Russia: A Country Study. Library of Congress, 1998, 34.

Khvoshchinskaya, Sofia. City Folk and Country Folk. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov, Columbia University Press, 2017, 7.

Pushkareva, Natalia. Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century. Translated by Eve Levin, Routledge, 2016.