Q&A: Philippe Met on The Cinema of Louis Malle

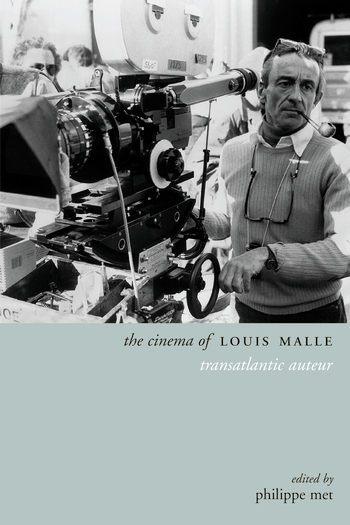

Louis Malle was the pioneer of the French New Wave and went on to an acclaimed transatlantic career. Today is his birthday and to learn more about this great film director, our Donovan N. Redd interviewed Philippe Met, editor of The Cinema of Louis Malle.

In this book, Philippe Met assembles a host of contributors that deliver a berth of essays capable of capturing the man that is Louis Malle, a man nearly impossible to pin down — a man in a constant state of reinvention.

Enter our raffle for a chance to win a copy of this book.

• • • • • •

Donovan Redd: Philippe, congratulations on publication! We’re enthused to share this much-needed project on Louis Malle. At the risk of asking you to repeat yourself, why Malle? Why now?

Philippe Met: Many thanks, Donovan. Your dual question is actually all the more relevant because it is at the very origin and at the core of this project. With Louis Malle we have a truly unique, if not unprecedented, body of work that was developed on both sides of the Atlantic. And yet, for reasons that have to do in part with ideological biases (the “stigma”, at least in France, of being born with a silver spoon in his mouth, his early albeit short-lived association with the French New Wave and the ensuing alienation from Cahiers du cinéma, etc.), in part with the controversial subject matter of some of his films, his output is sorely neglected from a critical point of view (both in France and in the US) while it definitely continues to enjoy popular notoriety in Malle’s native country. Hence an urgent need, I felt, for a comprehensive reassessment of his oeuvre before we reach a quarter-of-a-century mark after his premature demise…

DR: Following up, you mention in your introduction that part of what makes Malle so understudied is his intentional distance from his Nouvelle Vague contemporaries and his utter uncategorizable. What is it about Malle’s work that makes it so impossible to categorize?

PM: Malle’s work is difficult, if not entirely impossible, to categorize mainly because, while he is vastly considered a full-fledged auteur with unmistakable thematics and obsessions or a strong autobiographical thread running through his filmography, he systematically resisted and rejected the temptation of repeating himself, of making the same film twice. Not only didn’t he want to be pigeonholed, he always feared getting bored or blasé, or falling into a rut, and therefore constantly looked for new challenges. Along the way he successful tried his hand at various styles and genres, including an ongoing oscillation between or conflation of fiction and documentary, which sometimes vexed or confused critics who never knew what to expect from him.

DR: Since Malle can’t be categorized, you turn to three principles to make sense of Malle: (1) “intellectual curiosity and humanistic openness,” (2) “‘passion’ and ‘acharnement,’” and (3) “constant shuttling” between seemingly incongruous subjects and elements. Can you speak more about how these principles come together to inform Malle’s artistic practice?

PM: The keywords for me here constitute what might be perceived by many as a paradoxical riddle or an oxymoronic identikit : movement or energy and continuity or stability, permanence and renewal, dissipation and unity, heterogeneity and consistency. To pick one example: unlike other directors before or after him, his move to the US was motivated less by external factors (say, the German Occupation of France, the lure of Hollywood, etc.) than by a highly personal urge–to try new (ways of doing) things on many levels without ever truly settling down so as to remain on the edge, to maintain a high degree of receptiveness to the complexities of human society and the world around him (to which his love for documentary filmmaking is also ample testimony). The way John Guare explains how Atlantic City was made in record time, on an impulse but with an acute awareness of witnessing (and then recording, or fictionalizing, rather) a historical sea-change (in the great American tradition of a rise-and-fall narrative, or decline after the heyday and before rebirth) and a meticulous attention to structure and detail is a case in point.

DR: Thank you for that—it’s helpful for figuring Malle’s work as much as one can. Let’s move on to Malle’s conceptual framework and to his films. What would you say signals a film as unquestionably Malle’s work? What would need to be in a clip to make you exclaim, “THIS! This is Malle; Malle at his best!”?

PM: Always a tricky question, that one, and even more so in the specific case of Louis Malle–we go back to the auteurism quandary and the exigencies (and constraints) of variety (more than variation). And it is also contingent on what it is one looks for or pays attention to, first and foremost, when watching films and/or trying to gauge a filmmaker – is it form or content, narrative or visual style, themes or characters, history or philosophy, etc.? Because Malle was such a protean artist it is equally daunting to pinpoint a single element/moment and to identify a trademark “signature”. Since so many of his films were rightly or wrongly deemed provocative or “scandalous” at the time of their release I’d venture that Malle is perhaps at his best when he tackles those particularly sensitive or borderline moments – I’m thinking in particular of the incest/post-incest ending of Murmur of the Heart.

DR: What film would you point folks to if they wanted to gain a sense of Malle’s filmic poetics?

PM: Depends what you mean exactly by “filmic poetics.” There is certainly a general divide within Malle’s corpus between his more “mainstream” or accessible films (e.g., Au revoir les enfants) and his more obscure or experimental opuses (e.g., Zazie or Black Moon), but because of the scope and diversity of his output one might say that any film by Louis Malle is a good point of entry into his work. That said, this might be largely subjective but I believe Lacombe, Lucien is perhaps in many respects his most iconic film – the one that will give you an understanding of the range of Malle’s “poetics.”

DR: How do you think Malle’s transatlantic movement informed the ways in which he navigated his shifting sense of self?

PM: I’ve already tried to give an indication of this with one of your preceding questions, but I would point you and our readers to the interview I conducted with John Guare who not only scripted Atlantic City but was a close and dear friend of Malle’s until the end. Malle was an impressively cultured, cosmopolitan man and felt at ease in New York City, arguably even more so than when he was in Paris, if only because he could blend into the crowd, enjoy an enhanced sense of freedom, and feel energized by the possibilities proffered by a city that never sleeps…

DR: Is there a particular stage of Malle’s never-ending reinvention that sticks with you most? A period, a moment, a film, where you feel Malle was at his introspective and inventive best in the midst of his “existential restlessness?”

PM: This is clearly a biased answer since my chapter contribution in the book focuses on this film, but I think Le Voleur perfectly crystallizes a watershed juncture – an existential crisis – in Malle’s life and career while encapsulating a more general inclination toward introspection and melancholy in his personality amid outward agitation and restlessness. The fleeting moment when the burglar (as alter ego for the filmmaker), holding a lantern as he prowls through a benighted mansion, sees his almost ghostlike reflection in a glass door is for me a memorable example. The Fire Within also comes to mind–and so many others…

DR: I appreciate you being so open and insightful about Malle’s many fixation and many selves. Before we close out our interview, I have another question about the artistic matrix that is Malle’s catalog: what would you say the scores and literary references within Malle’s work tell us about his filmic fixations and personal exploration?

PM: Louis Malle was an avid reader and music enthusiast since childhood and all throughout his adult life. This is reflected in the kind of material he repeatedly sought, but sometimes failed, to bring to the screen (Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Queneau, Drieu La Rochelle, etc.) and his collaboration with writers (including Noble prizewinner Patrick Modiano) as well as the regular use of jazz scores (starting with the groundbreaking improvisation by Miles Davis on Elevator to the Gallows). For him literature, film, music were all part of his personal life, of artistic life in general – or just life, plain and simple.

DR: Final question, after fully bringing The Cinema of Louis Malle together, how has this project refigured how you remember Louis Malle, if at all?

PM: Working on this project simply consolidated my perception that Louis Malle’s oeuvre was indeed long overdue for a reevaluation within the context of not only French or American cinema but world cinema. It confirmed that his is a largely unique, incredibly rich and varied oeuvre that deserves to be rediscovered. I take a recent retrospective of his career at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris as a gesture in the same direction. My hope is that the book significantly and lastingly contributes to this trend and recognition.

• • • • • •

Once again, congratulations on publication and thank you for the many insights shared today. We’d like to remind our readers to enter our raffle for a chance to win a copy of this book and to check our blog tomorrow for an excerpt from The Cinema of Louis Malle.