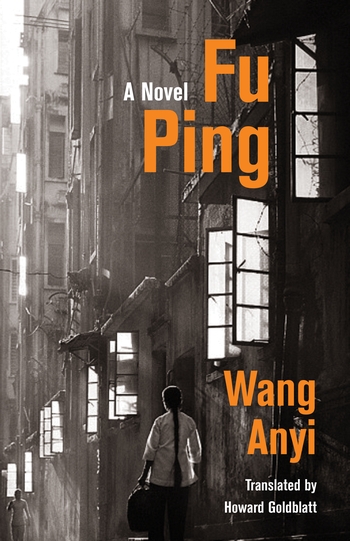

Q&A: Howard Goldblatt on Translating Literary Works and the Fiction of Wang Anyi

“Wang Anyi is one of the most critically acclaimed writers in the Chinese-speaking world.”

~Francine Prose, New York Times Book Review

Today’s Women in Translation Month featured title is Wang Anyi’s Fu Ping, translated by Howard Goldblatt. Fu Ping follows the titular character’s slow discovery of the alleys and side streets of Shanghai through glimpses into the lives of the working-class people who live there. In today’s Q&A, Howard Goldblatt—an internationally renowned translator of Chinese fiction—offers insight into Wang’s work in the 1980s and the challenges of translating fiction.

Enter our drawing for your chance to win a copy of Fu Ping!

• • • • •

Q: Your first translation of Wang Anyi’s work into English was the title novella to the collection Lapse of Time in 1988. Can you tell us a little about what led you to Wang, who was just emerging in the literary circle in China in the early 1980s?

Howard Goldblatt: “Lapse of Time” was, in fact, my first encounter with Anyi’s work. I knew only that she was the daughter of the pre-Cultural Revolution novelist Ru Zhijuan, but I was asked to read and then translate “Lapse of Time” by friend and fellow translator Gladys Yang. I was struck by how the story departed from the highly politicized grand narrative of the time, avoiding the prominent jeremiads that emerged from the decade of horrors. Wang was more interested in the quotidian concerns of people from all walks of life.

Q: What brought you to Fu Ping 30 years later? Has your relationship with Wang’s writing changed since then?

HG: I’ve never stopped reading works by Anyi, who represents the country’s southern cities and rural villages, but, owing to my association with China’s northern cities and writers—Xiao Hong, Mo Yan, and others—I have remained her fan, but not necessarily her translator, of whom she has had several. That changed when I happened upon this slender novel in a bookstore. As with so much of her writing, she focuses on the urban underclass, the nannies, garbage scow operators, handymen, peddlers, and more, whose lives are frequently contrasted with the middle-class and military families whom many of them serve. Anyi is a hopeful writer, projects a tone that sets her novels, in particular Fu Ping, apart from so much of the fiction from her peers.

Q: Both “Lapse of Time” and Fu Ping center around Shanghai in the 1960s. Do the two works have the same perspective on the city, or are there notable differences? What can readers learn about the city, present and past, from her novels?

HG: Shanghai, as far as I can recall, does not play as prominent a role in “Lapse of Time” as in Fu Ping. In the former, the city serves as the backdrop against which the story unfolds, whereas in the latter, you can almost argue that the city is a character itself. The flood she describes toward the end of the novel gives you a palpable sense that the city is alive and breathing, and that it, along with characters in the novel, propel the story forward. I’ve been a frequent visitor to Shanghai, and in reading her fiction, I have a recurrent image of a bustling commercial metropolis swirling around a quiet, keenly observant writer like a carousel, with fragments of its component parts spinning off to create a human kaleidoscope that then becomes her Shanghai. Here is how she has described her relationship with Shanghai: [It is] “the city I live in: covered over by my life, so that no matter how much distance I put between us, even if I’m looking down from the highest point, all that’s visible to me is my own heart. The city’s bright and shiny surface has always given off a whiff of cloying vulgarity, not to mention a sort of anomie. It has always been tainted by life.” The city comes alive in Anyi’s writing and provides the inevitability of the many dramas that take place there.

Q: You are also the primary English translator of Mo Yan, the Nobel Laureate in literature in 2012. Both Mo Yan and Wang Anyi use many local dialects in their fiction, and the ones they use are radically different. Do you find that to be a challenge during translation? How do you render those regional dialects into English while maintaining some sense of local specificity?

HG: The translator’s “challenge” is rendered largely moot by the individualized writing itself. Male-female, north-south, peasant-intellectual, the differences are clear in their work in Chinese. Every translation is a challenge for its own reasons, and a novel devoid of local expressions is not necessarily therefore easy to translate. Trying to replicate Chinese regional dialects in English is, I believe, a fool’s errand. What seems natural and yet idiosyncratic in the original will, if non-standard forms, structural and verbal, are forced upon the text, produce false equivalencies. Mo Yan will always be Mo Yan, in Chinese and in English, and Wang Anyi will always be Wang Anyi. The challenge in translating a series of works by an author, in my view, is deciding how much consistency of style to maintain in each one. That is, should everything by one author read similarly or should each one be different? I let composers like Beethoven be my model—when we hear a Beethoven symphony we can readily identity its composer, and yet each is distinctive, and one cannot accuse him of writing the same symphony over and over.

Q: There are many English-language translators of Wang’s work, and there’s certainly plenty of it to translate. What aspects of Wang’s writing do you hope that readers will take away from your own translations of her work?

HG: In Fu Ping, the realist narrative immerses the reader in stories of people living in a modern environment in the middle and beyond of the previous century, while largely holding on to traditionally conservative worldviews, and a broadly human one. Devoid of literary flourishes or gimmicks, it highlights the universality of human emotions and interactions with features that yet remain unique to the author’s hometown. It is one of those books whose portraits can draw a reader back for future readings. I hope that English readers will find her works engaging, as superb portrayals of human drama, and not as textbooks on China or tour guides to the city of Shanghai.

WITMonth sale! Save 30% on this month’s featured titles and more! Use coupon code WIT2019 at checkout!