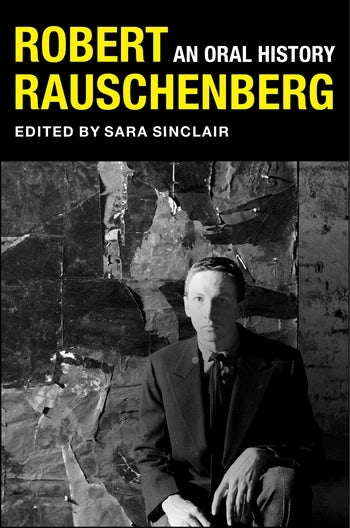

Robert Rauschenberg from the Cutting Room Floor

“The informative and entertaining voices of this solid work are as idiosyncratic as the artist himself. This is an excellent history for fans of Rauschenberg and mid-20th-century art.”

~ Publishers Weekly

Our celebration Robert Rauschenberg continues today with an inside look at Robert Rauschenberg: An Oral History. In this post, editor Sara Sinclair shares her favorite stories that did not make it into the book.

Enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book.

• • • • • •

Robert Rauschenberg: An Oral History is a work of collaborative oral biography; it was assembled through an editing process that put narrators in conversation with one another. One of the challenges in compiling the book in this way was that many great stories, or even great narrators, could not be included because there was no one we could edit them into conversation with. Here are a few of my favorite stories that didn’t make it into the book:

Celebrated gallerist Irving Blum on his decision to purchase Andy Warhol’s original set of thirty-two Campbell’s Soup Cans.

I ran out of the gallery and called Andy, and Andy said, “Come on over.” As I walked down a corridor to get where he was in the parlor room, there were three Soup Cans on the floor leaning up against the wall and one photograph of Marilyn Monroe torn out of a magazine like Photoplay, which he had pinned to the wall, and these three Soup Cans. Finally, I walk back and he was there and I said to him, “Hey. There are three Soup Cans on the floor.” He said, “Yep.” I said, “Why three? Seems redundant.” He said, “I’m going to paint thirty-two.” I said, “You’re kidding.” He said, “Not at all. I’m going to paint thirty-two.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Well, there are thirty-two varieties and in twenty years there’ll be fifty and I thought I would do them all. In any case that’s the idea.”

I said, “Do you have a gallery? Did you find a gallery since I was here last?” He said, “No, I have no gallery,” and I said, “What about showing them in L.A.?” And he thought, he hesitated—I could see he was thinking, well he did them in New York, his friends were there, one thing or another—and I took his arm and I said, “Andy, movie stars come into the gallery.” He loved that. He said, “Wow! Let’s do it!” That was it. That began my relationship with him.

In July of 1962 I showed all of the Soup Cans. Thirty-two paintings. I sold four or five, then had the idea of buying them and keeping them as a set, since that’s what they were, and Andy liked the idea. So I called the three or four people, including Dennis Hopper, that I sold individual paintings to and I was able to keep them all. I paid Andy one thousand dollars over a year and secured them.

Sidney Felsen, cofounder of the artist’s workshop and publisher of hand-printed, limited-edition lithographs, Gemini G.E.L. Rauschenberg would go on to produce more than 250 different prints with Felsen, but this is the story of their first collaboration.

We got to know Bob a little bit and so we asked him if he would come and do a project with us and he said yes. So in February of 1967, I pick him up at the airport. I said, “Do you have any idea what you would like to do?” And he said, “Well, I’m thinking about doing a self-portrait of innerman.” “Okay,” I say to myself, “what does that mean? I don’t know.” So, anyway, I didn’t ask him what it meant. I left him off at his hotel.

I picked him up in the morning and he said, “Do you have any friends that are X-ray doctors?” It just so happened that probably my closest friend from high school was an X-ray doctor so I took him to the doctor. Bob wanted to do an X-ray of his body and he wanted one plate—6 feet—of his whole body. We found out there is no such thing in the United States—except that Eastman Kodak in Rochester had a six-foot machine. But all X-ray machines are one-foot. He didn’t want to go back to Rochester so he had his body X-rayed in the six plates and he developed a print called Booster [1967], which was really his skeleton, so to speak. It was 6 feet tall and 3 feet wide. And it became, and still is, a classic in the print world. If you ask people what are some of the most important prints done in the United States in the last fifty or sixty years, everybody would include Booster. That was Bob’s beginning at Gemini. He did a series called Booster and 7 Studies [1967]. And, typical of him, Booster was the main image and then he took seven different pieces of Booster and put it on seven different plates and they were called Test Stone 1, 2, 3, and 4. So that became his first series at Gemini.

Janet Begneaud, Rauschenberg’s sister, is a big presence in the book, but this story, about her adventures as the Yambilee Queen, isn’t, and I love it.

“In Louisiana, we have festivals. It kind of is about the Catholic Church deal because they have what they call the blessing of the crops. There’s a shrimp festival, there’s a sugar cane festival, and Yambilee is the sweet potatoes of course. I was the Yambilee Queen and Bob just loved it. He just thought that was so, so way cool. But see, he loved me so much and of course I loved him back. So everything that I did that was good, he always kind of made note of it. So I do show up a good bit [in his work], especially with that crown.

But let me tell you a funny story about the Yambilee Queen thing. When we were in Malaysia, I went with him there and we were guests of the king and queen of Malaysia. On the way, we were first class, they had little orchids on the table, real ones, and I had never flown first class before. Not like that. And it was really, really fun and they were feeding us the whole time and of course those little Malaysian stewardesses were just gorgeous. They’re like little china dolls and they had little outfits. Anyway, we really were having a good time.

But on the way over there, we were told that in Malaysia it was not considered decent for a woman’s bosoms to show and your arms you’re supposed to have covered up. Well, this was summertime. For sure we didn’t have anything long-sleeved and to go to this one big function, it was a formal kind of thing and so it was kind of bosom-y. Bob said, “Don’t worry about it. We’ll buy you a sweater.”

So anyway, we went to this function and I didn’t wear a sweater. We went and were seated at a head table, and it was Bob and I and his entourage. Then across the way over there, they weren’t sitting on thrones, but their chairs were different than ours, I can tell you, because of the king and queen. Bob had stood up and he was very glib and well-spoken and so he’s telling them what a nice time we’re having and how beautiful their country is and to the king he said, “And your wife is so beautiful.” Which she was. And he said something about being a queen. And he said, “I brought my own queen.” So he reached down and grabbed me by the arm and stood me up and he said, “This is my baby sister Janet and she’s the Queen of the Yambilee.” Then he went on talking.

So then later in the evening we’re just sort of milling around and the king came up to me and he said, “I didn’t quite understand what your brother said. Where are you the queen?” I figured that it’s sort of comparable to homecoming queen or something, but I knew he wouldn’t get that one. So I really didn’t know what to say. So finally I just said, “Oh, Opelousas,” because the main part of the festival is in Opelousas. That’s the heart of the sweet potato country. Opelousas, Louisiana. But that was a big enough, funny word that I figured that would give him something to think about. And then I just went on talking and he went, “Oh.” So I don’t know if he thought about it or he might have gone home to see if he could find the country of Opelousas or whatever. I thought that was so funny.

He said, “But I brought my own queen.”