Erasing History: A Conspiracy Against Equality

By Alex George and S. Anand

“Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men is that rare achievement, a work that combines meticulous historical scholarship. . . with a passionate, persuasive call to action.”

~Wendy Doniger, author of The Hindus: An Alternative History

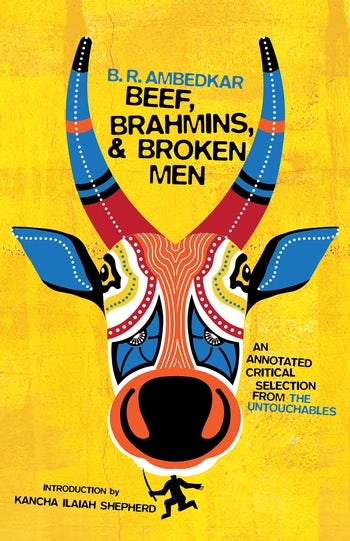

B. R. Ambedkar spent his life battling Untouchability and instigating the end of the caste system. In writing The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?, he noticed an absence of history. In today’s Black History Month post, Alex George and S. Anand, draw on the similarities between the American Civil Rights movement and the Dalit Emancipation Movement to illustrate how oppressors intentionally erase or refashion history to their benefit.

Enter our Black History Month drawing for a chance to win a copy of Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men: An Annotated Critical Selection from The Untouchables, by B. R. Ambedkar. Edited and annotated by Alex George and S. Anand.

• • • • • •

The movement for Dalit emancipation in the Indian subcontinent has over the years adopted many symbols from the Civil Rights Movement of African Americans: the Dalit Panther, founded in 1972; Dalit History Month; and a host of hip-hop artists emerging today, such as Arivu. This affinity is not merely a result of solidarity in oppression. It is also the result of a congruence of history—or rather a lack of it.

When Malcolm X adopted his new last name, he was pointing toward this lack. In rejecting the name given to him by slavers, he was showing us his history, the one that was brutally ripped away from him and his people, erased and emptied, leaving them with a present of oppression. This is the present that needed to be annihilated. In Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men, B. R. Ambedkar, statesman, lawyer, newspaper editor, economist, jurist, philosopher, and architect of the Indian Constitution, attempts to grapple with this very lack of history. Ambedkar was born into the Mahar “Untouchable” caste in a society that relegated 20 percent of its population to the bottom, forcing them to perform the most demeaning tasks in service of the Hindus—excluded, despised, bonded. He spent his life in trying to bring about a social revolution, trying to make the so-called upper castes, the Touchables, realize their complicity, trying to reveal the extent of the rot in the system and religion they treasured.

“In rejecting the name given to him by slavers, he was showing us his history, the one that was brutally ripped away from him and his people, erased and emptied, leaving them with a present of oppression.”

Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men is an annotated selection from Ambedkar’s 1948 book, The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?. What confronted him while writing it was an absence of history. Indian history has for the longest time been the story of the formation of a Brahmanical society. How things came to be as they are is often passed on as a story-poem-myth. The Mahar caste, to which Ambedkar belonged, was expected to perform duties for the village as part of the baluta system, free work for which they received “payment” such as the right to the dead cow’s carcass and hence its flesh and skin. Ambedkar investigates the origin of the Untouchables, setting aside even anti-Brahmin myths that Dalit narratives sometimes offer, however subversive they are.

Consider, for instance, a version of the history of untouchability from Telugu-speaking southern India offered from a Dalit perspective. G. Kalyana Rao, Telugu Marxist writer with a Maoist orientation, retells the Jamba Purana in his acclaimed novel Antarani Vasantam (2000, translated into English as Untouchable Spring). This story, claiming a Puranic status from around the fifth century CE, features the gods Parvati and Siva, among others. Chennaiah, miraculously born to Parvati, has the job of grazing Kamadhenu, the golden cow of the gods. One day, he has the urge to drink its milk. He asks Parvati, and she tells him to tell the cow of his urge. On hearing his request, Kamadhenu drops dead. If its milk is so sweet, how must its flesh taste, Siva and Parvati wonder. All the devas and devatas, gods and godlings, come to see and stand salivating around the dead Kamadhenu. But all of them together cannot lift its body. Chennaiah, at Siva’s behest, then summons his ancestor, Jambavan. He is stronger than all the gods and lifts the dead cow with his left hand. The gods then butcher the cow and instruct Jamabavan on how to cook it, asking him to make two halves of the meat. He does not heed them and cooks the entire meat in one pot. While stirring, he allows a piece of meat to fall to the ground, become muddied and impure. Chennaiah cleans it and puts it back into the pot. This angers the gods, and Siva curses Jambavan and Chennaiah: You will live in Kaliyuga, the Evil Age, eating the meat of dead cows and sweeping the streets forever. Heedless, Jambavan and Chennaiah eat the beef. And so it happens that in Kaliyuga, Jambavan’s progeny become Madigas, and Chennaiah’s children become Malas, two Dalit castes in South India.

“In an age when Hindus slaughtered and ate cows indiscriminately and practiced caste-based discrimination, Buddhism became the succor for the masses.”

But Ambedkar does not wish to counter myth with myth. He’s looking into a void for logical answers; as Ambedkar says, “[For the caste Hindus] writing history is a folly, for the world is an illusion.” He contends that the silences in history about how certain classes of people became Untouchable was a conspiracy against equality. Ambedkar presents us with two critical conceptual pieces of evidence—Buddhism and beef. Buddhism emerged as a counter to the excesses of Vedic Hinduism. In an age when Hindus slaughtered and ate cows indiscriminately and practiced caste-based discrimination, Buddhism became the succor for the masses. It was a tempering and uplifting force. Ambedkar tells the story of the appropriation of this religion and its subsequent decimation, the direct result of which was the creation of Untouchability.

Beef was the lynchpin in the formation of this balance of power. In appropriating Buddhism’s ethic of nonviolence in a zombified, farcical form, the Hindus needed a scapegoat (or scapecow, if you will). The Untouchables, who were originally the toiling classes, making up a majority of the Buddhists, and whose traditional job it was to dispose of the cow carcasses, became the enemy, ready for subjugation. Thus, the violent cow sacrificers became vegetarian, and those who had no choice but to work with carcasses and who could afford nothing other than beef became despised.

“In appropriating Buddhism’s ethic of nonviolence in a zombified, farcical form, the Hindus needed a scapegoat (or scapecow, if you will).”

India has an image world over as a vegetarian nation. The vegetarian fascistic state has now come into its own as a place where Dalits and Muslims are lynched, beaten, paraded, ghettoized, and humiliated for their occupations, which are often linked to the cow. India Spend, a policy research think-tank, reported that of the 123 instances of cow-related violence between 2010 and 2018, 98 percent occurred after the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power in 2014, helmed by Narendra Modi. The BJP’s ideological parent, the far-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, in its journal Panchajanya justified the lynching with a cover story “Vedas Order Killing of the Sinner Who Kills a Cow” (October 21, 2015). Brahmanism, which follows its fascist Western counterparts in conjuring up shadowy enemies, sees no absurdity in a cow becoming more valuable than human life.

All voices that rail against the establishment have become antinationals, enemies, extremists. A Brahmanical regimen is now being imposed where what we eat, what we say, and what we think are policed and controlled systematically by state and state-linked operators. This is Gandhi’s Ram Rajya on steroids—insecure and brash, meting out violence with might but without thought. It would do us good in this time to follow Ambedkar in his sleuthish quest, where he reveals those symptoms in the very psyche of the collective called India, driven by the force called Hinduism, which has made this violence the constitutive power of the nation.

For Ambedkar the absence of historical evidence about the origin of Untouchability is symptomatic of the corrupt nature of Hindu morality. Its existence does not perturb the Hindus because their moral universe is constructed on the idea of inequality. In the preface he writes: “In any other country the existence of these classes would have led to searching of the heart and to investigation of their origin. But neither of these has occurred to the mind of the Hindu. The reason is simple. The Hindu does not regard the existence of these classes as a matter of apology or shame and feels no responsibility either to atone for it or to inquire into its origin and growth.”

“Those from the oppressor classes have a subjectively justified interest in erasing the history of the oppressed, and in this erasure the world forgets the injustice it is capable of.”

This Black History Month, let us remember what Ambedkar realized in writing this book. Those from the oppressor classes have a subjectively justified interest in erasing the history of the oppressed, and in this erasure the world forgets the injustice it is capable of. In this case we must not only continue to write these histories but also boldly reclaim and rewrite those histories that the oppressors tore away from us and fashioned to their benefit.

We leave you with some food for thought: a simple Dalit beef recipe documented by the artist Rajyashri Goody:

Jai Bhim!