Rape on Campus: The Title IX Revolution

“Anti-rape activism is on the vanguard of transferring the blame and responsibility from individuals to social systems and institutions. If ours is a rape culture, then the solution must also address the culture of sexual violence that perpetuates sexual assault and gender-based violence.” — Kelly Oliver

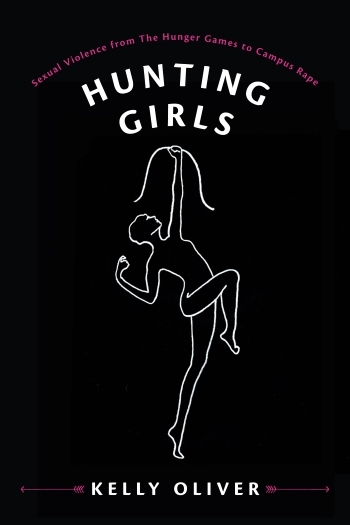

This week, our featured book is Hunting Girls: Sexual Violence from The Hunger Games to Campus Rape, by Kelly Oliver. For the final post of the feature, we are happy to provide an excerpt from “Rape on Campus: The Title IX Revolution,” an article by Kelly Oliver that originally appeared in The Philosophical Salon.

Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway for a chance to win a free copy of Hunting Girls!

Rape on Campus: The Title IX Revolution

By Kelly Oliver

Title IX legislation, associated primarily with equal opportunities for girls in high school and college athletics, has become a turning point in discussions of sexual assault. Until recently, the greatest impact of the 1972 Title IX legislation had been to ensure girls and women had access to sports. Although introduced to stop discrimination in higher education, Title IX became the hallmark of women’s athletics, to the point that today there is a women’s sporting clothing company named Title Nine, and last year President Obama spoke about the importance of Title IX for girls in terms of his own experience coaching his daughters’ basketball team and the confidence it gave them. Initially, Title IX was used to secure funding for girls and women’s sports, which had been lacking until required by this Federal statute.

On April 4, 2011, The United States Department of Education sent a “Dear Colleagues Letter” to institutions of higher learning, shifting the focus from college athletics to educational environment, specifically naming sexual violence as prohibited by Title IX. The letter defines sexual violence as “physical sexual acts perpetrated against a person’s will or where a person is incapable of giving consent due to the victim’s use of drugs or alcohol,” including “sexual assault, sexual battery, and sexual coercion,“ and makes colleges and universities responsible “to take immediate and effective steps to end sexual harassment and sexual violence.”

Much of the recent attention paid to sexual assault as a Title IX violation is the result of a lawsuit filed against The University of North Carolina in 2013 by Annie Clark and Andrea Pino, two undergraduates raped during their first weeks on campus. Both reported the attacks to the University, but they claim their statements were ignored or belittled. These two courageous women have made headlines for their anti-rape activism after they founded EROC (End Rape on Campus) to help other women file Title IX lawsuits against universities across the country. Their use of Title IX has changed the terms of discussions over sexual assault on campus. This strategy has forced even those who insist, “rapists cause rape” to rethink isolating perpetrators from the culture that protects them.

There are at least two profound philosophical implications to be drawn from this approach to sexual violence, signaling a major shift in how we view responsibility. First, educational institutions are held responsible for creating the environment allowing, if not fostering, sexual violence; or, conversely, and more to the point, they are held responsible for creating an ethos fostering women’s education, which is not possible when one out of four college women is sexually assaulted and gender-based violence is a constant threat. The new use of Title IX marks a dramatic change in the attribution of responsibility for sexual assault and rape. Rape survivors across the country are filing Title IX lawsuits against their colleges and universities for allowing serial rapists to remain on campus, making the environment unsafe for female students. This strategy targets the educational institutions that harbor rapists rather than the rapists themselves and therefore holds schools responsible for sexual assault on campus. Rather than excuse the problem with the argument that a few bad apples spoil the whole bunch, this approach looks to systematic policies of disavowal and denial, of a dearth of attention to the problem, and a lack of consequences for perpetrators, along with the ways in which fraternities and sports culture perpetuate rape myths that women want to be raped or that blame the victims. In a society that values individual over institutional responsibility, this is a turning point. How successful it will be is another matter. But, conceptually, it forces us to think about the culture that spawns serial rapists on campus, and protects perpetrators instead of survivors.

Second, the use of Title IX in cases of sexual assault on campus switches the focus away from individual victims to gender-based violence. Rather than single out women as random targets of assault, or, as it happens too often, blame them for their own attacks through suggestions that they were asking for it by wearing provocative clothes, behaving in certain ways, or drinking, the focus shifts to the environment in which women are under a constant threat of being sexually assaulted. Just as the shift away from individual perpetrators forces us to concentrate on the culture or ethos that produces sexual assault and serial rapists on campus, the shift away from individual victims forces us to focus on gender-based violence and the culture that targets women for sexual assault.

Title IX as a strategy to address sexual violence against college women heralds a watershed in the way we view responsibility. Anti-rape activism is on the vanguard of transferring the blame and responsibility from individuals to social systems and institutions. If ours is a rape culture, then the solution must also address the culture of sexual violence that perpetuates sexual assault and gender-based violence.

The irony is that, while anti-rape activists and survivors are using Title IX to force colleges and universities to address the problem of sexual violence on campus, this same piece of legislation is also being used to shut down discussions of rape on campus, the very kinds of dialogue necessary to combat rape myths and rape culture. The risk is that educating about such violence itself becomes a “trigger” for past trauma as students demand safety not only from harmful deeds, but also from any talk of sexual assault. This makes Title IX a double-edged tool in addressing this issue. We could speculate that turning Title IX against those on campus who speak out against this serious problem is actually an attempt to combat this dramatic turn in thinking about responsibility and who — or what — is responsible for gender-based violence.

Title IX has gone from addressing funding and quantifiable differences between resources spent on men’s and women’s athletics and educational programs, to dealing with the ethos of educational institutions in terms of whether or not they empower girls and women. This is a first step in moving from concerns with mere formal equality in education to social justice for women. At least, as long as we use Title IX to open up rather than shut down discussions of rape culture and the contributions of rape myths, sexism, and hostility towards women to the prevalence of sexual violence.