Trump's Strange Loves

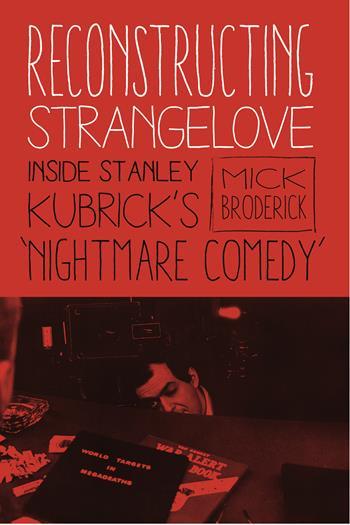

This post is part of an ongoing series in which Columbia University Press authors look at the implications of the result of the 2016 presidential election. In this post, Mick Broderick, author of Reconstructing Strangelove: Inside Stanley Kubrick’s “Nightmare Comedy”, discusses how Dr. Strangelove is and has been used in US politics:

Trump’s Strange Loves

By Mick Broderick

There has been much consternation recently concerning President Trump’s access to the American nuclear arsenal, the missile control codes (carried in the briefcase-sized “football”) and his personal authorization card (the “biscuit”). As newly anointed Commander-in-Chief, Donald Trump now wields near-apocalyptic power, literally at his fingertips. Throughout his appointed four-year term he can at any time – to invoke Robert Oppenheimer and the Bhagavad Gita – “become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Only a few minutes from committing to such action nearly a thousand nuclear weapons stationed on high alert could be unleashed and no one is legally empowered to stop him.

In reality, this is business as usual; same as it ever was. Trump’s supreme authority is constitutionally entrenched, with the continuity of executive power stemming back decades. What has changed, however, is the new President’s predilection for impulsively tweeting on foreign policy matters, amongst other things, into the wee hours. Now in office Trump continues to fire-off intemperate remarks at his whim and those missives are instantly accessible across the globe. When Ronald Reagan quipped before a radio broadcast during a microphone test in 1984 that he had just “signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever … we begin bombing in 5 minutes”, it was quite sometime before the audio was leaked to the public. Imagine the effect of a tweet from President Trump along similar lines, without the (comic) inflection of the spoken word or the corresponding audible guffaws from nearby presidential staff. Although largely symbolic given the Republican control of the Executive and both Congressional houses, moves are now underway by Democrats to curb any Presidential nuclear first strike order, by mandating that Congress must first declare war. Earlier, Trump had ranted at the Republican Congressional leadership to “Go nuclear!” against his Democrat rivals.

Critics of Trump were raising such concerns well prior to his election. His chief competitor, former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, and then incumbent POTUS, Barack Obama, repeatedly warned voters of Trump’s imprudent, if not reckless, capacity for spontaneous outburst. Questioning Trump’s temperament during her Democratic Convention speech Clinton stated, “A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man we can trust with nuclear weapons.” Obama had earlier categorized Trump as a person who “doesn’t know much about foreign policy or nuclear policy […] or the world generally.” More acerbically, Obama noted that Trump’s intolerance of criticism made him both vulnerable and dangerous: “if somebody can’t handle a Twitter account, they can’t handle the nuclear codes. If somebody starts tweeting at three in the morning because [Saturday Night Live] made fun of you, then you can’t handle the nuclear codes.”

With his repeated invective leaked so casually from the White House, Trump’s capacity to act rationally is being seriously questioned. There are now growing calls to examine the possibility of impeaching Donald Trump by invoking the 25th amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment permits a Vice President (with a majority of principal officers of the executive) to declare the President “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office,” thereby enabling the V.P. to “immediately assume […] the office as Acting President.”

Just prior to becoming U.S. President Trump repeatedly asked security experts since America had nuclear weapons, why he couldn’t use them? Around this time Trump called for a new and accelerated arms race to “greatly strengthen and expand [U.S.] nuclear capability”. More recently in a call to Vladimir Putin the President denounced the existing bilateral New START arms reduction treaty as a “bad deal”, one favoring Russia. He also ominously tweeted that Iran had been “formally PUT ON NOTICE” over a ballistic missile test.

Trump’s historical forbear in this regard was another maverick from the establishment’s margins who rose rapidly and unexpectedly to become the Republican Party’s presidential nominee. In 1964 critics of Senator Barry Goldwater mercilessly depicted him as a warmonger and potential instigator of a future nuclear conflagration. LBJ’s campaign team released a devastating television advertisement depicting a young girl pulling petals from a daisy before the screen was engulfed in a series of atomic explosions. The commercial implied that Goldwater’s belligerent capriciousness might lead to just such a cataclysm.

What helped cement the ongoing tone of these political barbs was the visible and vocal influence and power of key operatives within the military-industrial complex, ultimately feared but paradoxically bolstered by President Dwight Eisenhower during his eight years in office. Those beholden to this nuclear mindset were starkly rendered in Stanley Kubrick’s landmark film Dr. Strangelove: or, how I learned to stop worrying and love the bomb (1963). Kubrick’s genius was to blend documentary hyper-realism with biting satire to portray a deeply paranoid individual with command and control over nuclear weapons who instigates a deliberate (though unauthorized) nuclear attack. Counseling the President in the movie, senior Pentagon hawks immediately advocate an all-out nuclear strike, noting dismissively that the retaliatory Soviet reprisal would merely kill 10 to 20 million Americans “depending on the breaks”. The President’s principal nuclear adviser, an unreconstituted Nazi – the eponymous Doctor Strangelove – is shown to hold considerable clout over both politicians and military. Strangelove’s cold war vision of “preserving a nucleus of human specimens” underground after the global holocaust is now fueling the Trump era’s mega-rich who pursue “luxury bomb shelters” and “billionaire bunkers” built by elite “doomsday preppers”.

So potent has been the influence of Dr. Strangelove over the decades and across successive U.S. administrations, that since the film’s 1964 release, from President Johnson onward, every U.S. leader and many of their nuclear policy advisers, military commanders, and Secretaries of State and Defense, have been frequently subjected to ridicule as surrogate Strangeloves. From the pin-back button lampooning LBJ (“Strangelove Lives”), and Henry Kissinger’s assumed inspiration for the titular character, to online memes featuring George W. Bush and Barack Obama riding H-bombs à la Slim Picken’s as Major Kong, such iconic Strangelovian tropes have provided an easy cultural shorthand to metonymically conjure the latent impulse towards Armageddon underpinning nuclear deterrence, alongside the subterranean tendency towards fascism redolent in marginal American politics.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s President Richard Nixon deliberately fostered the impression amongst foreign powers that he (and Henry Kissinger) might just be “crazy” enough to engage in nuclear “interdictions” in Vietnam, and elsewhere directed against the Soviet Union. It became ultimately known as the “Madman Theory” – the diplomatic tactic of threatening excessive or extraordinary force to intimidate geopolitical opponents into acquiescence or submission. Today, Trump’s rhetorical and policy postures may indeed be similarly contrived. Nevertheless, the appointment of an “alt-right”, “anti-Semitic and white supremacist” apparatchik like Stephen Bannon to Trump’s National Security Council – effectively relegating the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and the Director of National Intelligence to lesser roles – eerily echoes Dr. Strangelove’s fictional ascendancy to power as the world descended into a thermonuclear maelstrom.