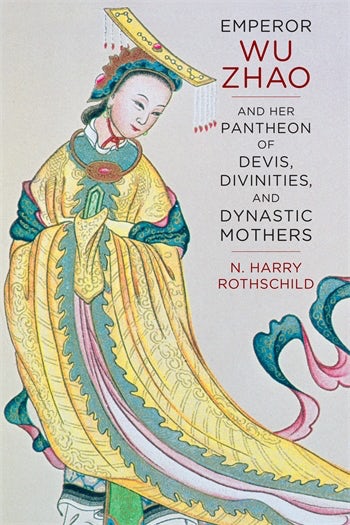

5 Ways That China’s First and Only Female Emperor Wu Zhao Reimagined Traditional Female Roles to Invent a Novel and Unique Vision of Emperorship!

Wu Zhao (624-705) was the first and only female emperor in Chinese history. Given the predominantly patriarchal and androcentric confines of medieval China, her singular ascendancy was wildly improbable. Even stranger, perhaps is one of the strategies she employed to progressively consolidate her power as empress (655-83), grand dowager (684-690), and ultimately as, emperor (690-705). In a society where women were sequestered in an inner, domestic sphere, where a woman wielding political power was viewed as contravening both the natural and human orders (an abomination akin to hens crowing to greet the dawn), she paradoxically discovered and took political advantage of deep cultural reservoirs of female potency to amplify her sovereignty. At first glance, this may strike one as a rather poor and misguided political tactic. Yet this strategy of fashioning an eclectic and flexible pantheon of “female ancestors” proved remarkably useful to Wu Zhao, first in justifying her rising court influence as empress and dowager-regent and later in her efforts as emperor to administer and preside over a multi-ethnic, pluralistic empire of 100 million. Let’s explore five reasons this seemingly wrong-headed approach proved surprisingly effective in Wu Zhao’s unprecedented establishment and maintenance of imperial power.

1. Motherhood

“In Chinese tradition, tremendous power was vested in motherhood. Given the central import of filial piety in the Confucian tradition, mothers, especially grand dowagers, were accorded great respect.”

Women were subordinate to men in the Confucian tradition, but to an even greater extent, youth submitted to age. A doughty sexagenarian by the time she assumed the throne and established her Zhou dynasty in 690, with seniority, experience, and social position, Wu Zhao possessed the gravitas to proclaim herself a “mother of empire.” To help build this image of a powerful mother, Wu Zhao, and her rhetoricians siphoned the cultural energies and collective maternal force of past celebrated cultural icons like Mother Li, the divine and powerful mother of Daoist sage Laozi; Māyā, the mother of the Buddha; and dynastic ancestress Jiang Yuan, the mother who miraculously birthed the first male ancestor of the Zhou dynasty of old.

2. Affiliations with Ancient Goddesses

“Framed in elegant and flamboyant terms by her most capable propagandists…the affiliation between Wu Zhao and primordial mother-goddess Nüwa was broadcast widely—carved on monumental stelae, announced to court via memorial, and reiterated time and again in the female sovereign’s majestic imperial titles.”

In Wu Zhao’s time, shadowy vestiges of ancient goddesses remained, maintaining a vital presence in the popular imagination. To no small extent, she was able to tap into this deep, culturally-embedded vein of mythic female potency, recovering and reclaiming the lost energies of these female divinities. As empress, Wu Zhao honored Silk Goddess Leizu—silk weaving was the defining vocation of women (“men plow and women weave,” goes the proverb)—leading a wider circle of women in public and visible ceremonies. Poetic associations between the local goddess of the Luo River—the riparian source of a cryptic diagram revealing the secrets of statecraft—helped elevate the profile of her chosen Divine Capital, Luoyang, long overshadowed by the grand city Chang’an to the west. These well-known goddesses—often tactically uncoupled from male counterparts and operating independently—helped burnish and exalt Wu Zhao’s image.

3. Association with a Glorious Collection of Talented and Capable Women

Wu Zhao (a widow herself) skillfully deployed a quartet of strong-willed and wise widows from Biographies of Exemplary Women, women who had been renowned for a millennium for the sage counsel they offered their sons on Confucian principles like public-mindedness, loyal service to the state, and even the art of governance.

To justify and normalize her political presence, Wu Zhao populated her pantheon with eminent talented, and capable women from the past who had played political or administrative roles. Mother Wen, wife of the founder of the original Zhou dynasty that marked China’s idealized Golden Age, was one of the “ten ministers” of her husband, King Wen. Wise mothers like Lady Ji of Lu and the Mother of Mencius used weaving to instruct wayward sons. A political manual she promulgated celebrated stalwart mothers of generals who used principle and moral suasion to teach their sons principles of martial leadership. The repeated appearance of these women in her rhetoric and rites helped overcome the deeply-embedded cultural notion that women were ill-suited for involvement in court and politics.

4. Devis from a Popular “New” Region

Just months before Wu Zhao inaugurated her Zhou dynasty, political propaganda was widely circulated to show that she was a universal Buddhist wheel-turning monarch and the avatar of Vimalaprabhā, a goddess that the Buddha had prophesied to be reborn as an earthly female sovereign.

Confucianism, the ideology of order and hierarchy at the heart of society, had a hard-wired patriarchal core. Wu Zhao’s Li in-laws, the Tang dynastic family she sought to supplant, claimed descent from the founder of Daoism. Thus, Wu Zhao naturally looked to Buddhism. Rising in popularity in her time, Buddhism crossed ethnic boundaries (Chinese and non-Chinese people alike embraced the faith), spanned the entire spectrum of social classes (nobility and common folk alike thronged to Buddhist festivals and fairs), and crossed gender lines (not only was the faith popular among women in the Tang empire, there was a growing order of Buddhist nuns). The pan-Asian faith well-suited to the cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic empire over which Wu Zhao presided.

5. Building a Flexible Pantheon of Female Political Ancestors

An “illustrious bevy of goddesses and cultural luminaries helped normalize Wu Zhao’s own political eminence: the woman emperor simply seemed a present-day extension of this glorious pantheon of female political ancestors.”

Wu Zhao’s broad and pluralistic pantheon of women provided ideological flexibility, allowing her to select an apt paragon or suitable divinity for each stage of her fifty-year political career: exemplary wives and ideal mothers helped add luster to her role as empress, strong-minded women with political experience lent validity to her regency as a grand dowager presiding over the court, and celebrated deities shed beatific radiance on her emperorship.

“Wu Zhao’s growing network of female “political ancestors” served to buttress and validate her person and her unique role as female emperor, because the presence of these women provided a sense that these familiar women always had been and always would be politically eminent.”

Though this formation of a pantheon of ancient mother-goddesses, exemplary Confucian women, Buddhist devis, and local cultic deities and was certainly not the only strategy Wu Zhao employed to ascend to the throne—to grasp and maintain political power—it played a significant role in the construction of her unique and idiosyncratic brand of authority. The preponderance of connections between female sovereign and the women of her pantheon, articulated sometimes with subtlety, sometimes with pomp and fanfare, served as a sort of composite apotheosis, imbuing Wu Zhao with an aura of the divine.

Predictably, in the Confucian historiographic tradition Wu Zhao is painted as caricature of ruthlessness, sadism, licentiousness, and extravagance. The multi-faceted image of the woman emperor that emerges in this study is starkly different: Wu Zhao was a master politician and a capable rhetorician possessing such a nuanced grasp of Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, and folklore that she was able to, as circumstance demanded, position herself as the latter-day incarnation of an archaic mother goddess, as the embodiment of the eminent and capable mothers revered in Confucian tradition, as the earthly conduit of silk-weaving goddess or a female river deity from poetry and folklore, as the prophesied coming of a chosen Buddhist devi who would reign over the country as a Cakravartin (a universal Buddhist sovereign), or style herself as the Queen Mother of the West, the greatest of the Daoist deities.

This is but a trailer, glimpse, a taste! For the whole of the movie/picture/feast, check out Emperor Wu Zhao and her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers.